Music Without Borders: Protesting While Dancing with Charly García

García’s seamless combination of energetic rhythms and protesting lyrics not only represented the sentiments of Argentine youth during his extensive career, but also cemented him as “the godfather of Argentine rock.”

Music has the power to transport listeners to cultures and places different from their own. In Music Without Borders, our writers introduce you to international artists, bands, and genres that explore the sounds that bring us together.

Written by Valeria Mota

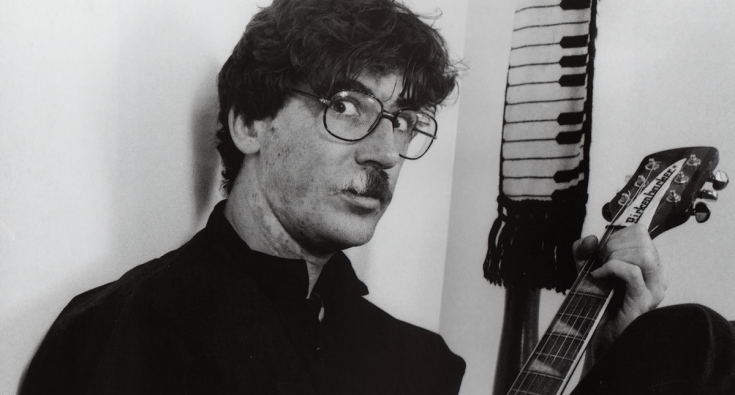

Photo courtesy of Latino Life

The 1966 coup d'état in Argentina marked the beginnings of a totalitarian dictatorship and heightened the nation’s political turmoil. One of the laws during this time was one year of mandatory military service for all young men, including twenty-year-old Charly García, who was drafted for service in 1971.

Like many young men, García absolutely despised his year of military service, attempting to escape his draft by feigning physical and mental illnesses. García’s animosity for the Argentine government fueled the young man’s voice to protest the country’s injustices through music, ultimately cementing him as an iconic Argentine musician.

Born in 1951, García immediately proved himself to be a musical prodigy, learning to play common piano melodies by ear. He became a huge fan of the Beatles in his youth, which led to a friendship with his high school classmate, Nito Mestre. Together, Mestre and García created the musical duo, Sui Generis, which officially formed after García returned from his mandatory military service. García’s military experience filled his mind with ideas that would push Sui Generis to the spotlight of early ’70s Argentine music. With the Buenos Aires’ native variety of instrumental abilities alongside Mestre’s flute and backing vocals, the duo quickly made their first hit, “Cancion para Mi Muerte” (“Song for My Death”). The reflective track was inspired by the time García took a bottle of amphetamines to fake his way out of his military service.

Sui Generis cultivated their passionate folk-rock style from the beginning of their career to its end. Their last album, Pequeñas anécdotas sobre las instituciones (“Small Anecdotes about the Institutions”), specifically focuses on criticizing fundamental institutions, including the army. The Sui Generis leader details his military experience in the song “Botas Locas” (“Crazy Boots”): “Yo forme parte de un ejército loco … pero mi amigo hubo una confusión /Porque para ellos el loco era yo” (“I was part of a crazy army … But my friend, there was a confusion / Because for them the crazy one was me”). Despite the group’s popularity, García ultimately left Sui Generis because of his label’s lyrical censorship, ultimately pushing him to take on more forceful forms of protest with his music.

After a brief yet commercially unsuccessful stint with the instrumental band La Máquina de Hacer Pajaros (The machine of making birds), the musical prodigy founded Serú Girán in 1978, which would end up being his most successful collaborative project. While the band’s self-titled debut was not well received, their 1979 sophomore record, La grasa de las capitales (“The Grease of the Capitals”) ultimately cemented their national popularity. The word “grasa,” which directly translates to “grease,” is Argentine slang for “tackiness,” so the title’s most accurate translation ends up being The Tackiness of the Capitals, which is exactly what Serú Girán poignantly critiqued. Paired with masterful bass and guitar solos, García’s songwriting was stronger than ever as he critiqued the superficiality of Argentine culture. The album’s title track opens with the verse “¿Qué importan ya tus ideales? / ¿Qué importa tu canción? / La grasa de las capitales / Cubre tu corazón” (“What do your ideals matter now? / Who cares about your song? / The grease of the capitals / Covers your heart”), clearly calling out the Argentine “capitals” for their lack of real moral values. As the face of the band, García made a name for himself as a musical innovator and protester from his effortless ability to pair new wave production with powerful social criticisms.

Serú Girán eventually disbanded in 1982, which allowed García to begin his solo career — which, out of all of his endeavors, marked him as an influential figure in Argentine rock and Latin American music. García’s solo career was the most commercially and critically successful of all his musical projects. Further, it also marked a point in his career when his instrumental experimentation and lyricism shined the most, with the former Serú Girán leader now leaning towards an even more explicit and brash approach to musical protest.

García’s 1982 solo debut was a double LP named Pubis Angelical/Yendo de la cama al living (“Angelical Pubis/Going from The Bed to the Living Room”). The first disc, Pubis Angelical, was García’s score for the 1982 film of the same name, but his official solo debut was the second disc, Yendo de la cama al living. The album encapsulates the fears of living under a military regime, resonating with long-time fans and new listeners. The album’s biggest hit at the time, “No Bombardeen Buenos Aires” (“Don’t Bomb Buenos Aires”), was a direct plea to the British to not bomb his hometown over the Falklands conflict. García’s use of catchy synthesizers and fast drum fills has all the marks of a radio hit, even if the song tackles a fearsome subject. In one of his concerts at the Estadio Ferrocarril Oeste, the multitalented keyboardist had props to simulate the Buenos Aires skyline as he sang “No Bombardeen Buenos Aires,” and concluded the show by having fireworks destroying the prop skyline.

García continued innovating with both new wave and synth-pop after his debut. With a quick trip to New York and sessions at the iconic Electric Lady recording studio, García wrote and produced what would soon be considered his magnum opus, Clics Modernos (Modern Cliques). Although many of García’s previous endeavors featured layered production and instrumentals, Clics Modernos took a more bare-bones approach, which allowed García’s keyboard and vocals to shine. The opening track, “Nos Siguen Pegando Abajo” (“They Keep Hitting Us Below”) is García’s most popular song to date and probably his most direct attack against Argentina’s totalitarian government. He describes a young man being persecuted by law enforcement, relating it to the country suffering under the military’s abuse of power: “Miren, lo están golpeando todo el tiempo / Lo vuelven, vuelven a golpear / Nos siguen pegando abajo” (“Look, they’re hitting him all the time / They keep, keep hitting him / They keep hitting us below”). Thematically, the entire album discusses authoritarian regimes, but the majority of the songs have upbeat, dance-inducing melodies. By delving into different topics but keeping a consistent, danceable pop-rock sound, Clics Modernos stands out as the musical activist’s most authentic opposition to authoritarianism, and as his most commercially and critically successful project.

In December 1983, a month after the release of Clics Modernos, the newly appointed Argentine president Raúl Alfonsín began the persecution of authoritarian leaders, marking the end of Argentina’s military dictatorship. Clics Modernos proved García’s impeccable ability to match entertaining rhythms with serious, political lyrics, and he continued using this talent for the rest of his career. Even though the regime was technically over, the “Canción para Mi Muerte” singer continued to write about life under a dictatorship in songs like “Demoliendo Hoteles” (“Demolishing Hotels”), where García discusses living amongst “fachistas.” However, despite its serious, political lyricism, the song is upbeat and features fun chord progressions and explosive drum fills.

Over 40 years later, Charly García remains an Argentine icon, influencing artists like Fito Páez, who began his career as García’s backing pianist. In 2021, Argentina’s government organized an event to celebrate García’s 70th birthday, where García played some of his greatest hits. The fact that the same government García so vehemently opposed ended up honoring his legacy shows his impact in Argentina and serves as inspiration for the rest of Latin America. Even though Argentina’s current political state differs from the past, Charly García’s innovative discography continues to encourage listeners to speak up for their beliefs — even if they do it while dancing.