Steal Like an Artist: How Cher Wrote Kanye

The influence of the “Goddess of Pop” on one of the most iconic rappers of the last two decades is a testament to the music industry’s common practice of borrowed time.

Written and illustrated by Emma Tanner

I happened across it. A mistake, you could say. A weird coincidence that only happens to the select few. A musical whim, a fated discovery.

It was a forgettable afternoon, and I was bored. Randomly, I had decided to scroll through Spotify for some new sounds. Straying far from my usual top picks of obscure indie boy bands and predictable Kanye bops (I’m a 21st-century teen, what can I say?) I took a dip into some throwback sounds and clicked on a playlist of 60s music in an effort to expand my musical range.

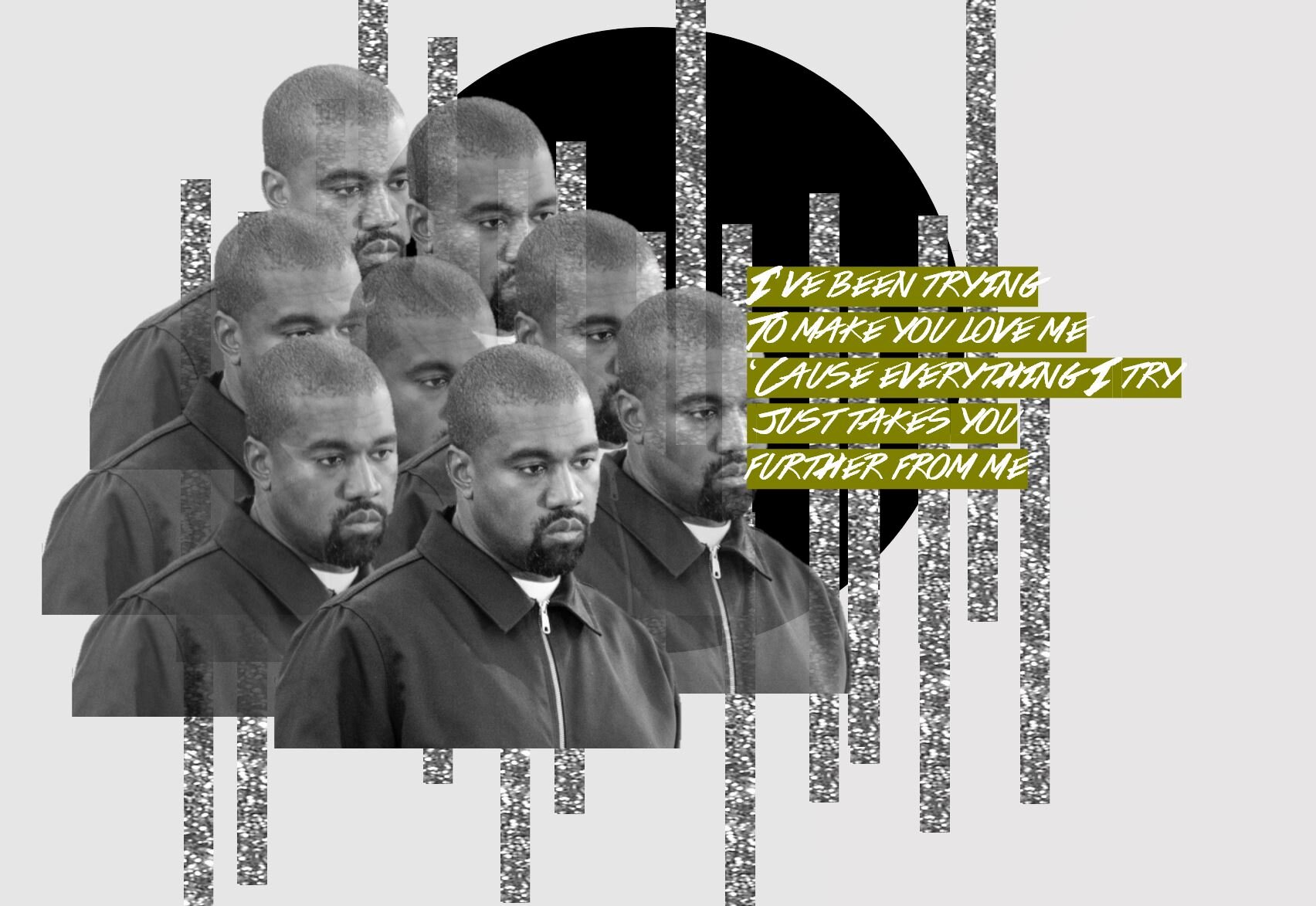

I soon found myself listening to “Take Me For A Little While,” a track off Cher’s 1968 album Backstage. Never heard of it? Neither had I. The drum-heavy track started out with an upbeat tune, and Cher’s smoky voice lulled through my headphones with the opening lyrics “I’ve been trying / to make you love me / but everything I try / Just takes you further from me.” I immediately paused the track — the lyrics sounded weirdly familiar.

Kanye. I knew those lyrics from Kanye. Those exact lyrics are the backbone of “Ghost Town,” a collaboration with PARTYNEXTDOOR off his 2018 album, ye. Stripped from the heavy drum beat of Cher’s track and layered over a heavily synthetic-sounding electric guitar loop, it was different, but startlingly recognizable. Kanye had made the opening lines of a 40-year-old song into the focal point of a track that teenagers scream out the open windows of their 2012 Ford Escapes on a night out with friends.

But Kanye isn’t the only one. The practice of borrowing lyrics and sounds permeates throughout the music industry. There are obvious similarities often drawn between major hits like Queen’s “Under Pressure” and Vanilla Ice’s “Ice Ice Baby,” to lesser known grabs like Jason Derulo’s memeified hit “Whatcha Say” forming its chorus around a snippet of Imogen Heap’s “Hide and Seek.” Even the “ABC” song shares a tune with “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star.”

In the age of royalty-free music and copyright laws that penalize your favorite Youtubers for using a 10-second snippet of someone else’s song, it comes as a bit of a surprise that so many blatant examples of borrowed sounds exist in the music industry. Inspiration is one thing, but interpolating lyrics or beats is a whole different musical playing field.

Take the 2015 copyright battle over Robin Thicke’s “Blurred Lines” as a $5.3 million example. After the song featuring Pharrell shot to the top of charts and determinately held its stance in just about every radio station’s queue, Marvin Gaye’s children sued the duo for copyright infringement of Gaye’s 1977 hit “Got to Give It Up.” Listen to the two and you’ll find that the rhythm is undoubtedly similar, with Thicke and Pharrell’s version throwing a few drum kicks and exclamatory shrieks on the decades-old beat that is the base of both songs.

The ruling that awarded $5.3 million and half of all future royalties earned by “Blurred Lines” to Marvin Gaye’s estate proceeded to spark an uproar in the music industry, with more than two hundred artists proclaiming their support in favor of Thicke and Williams’ side of the legal battle. Musicians among the likes of Train, Weezer, Hans Zimmer, Fall Out Boy, and Jennifer Hudson called for an overturn of the verdict, claiming that such an allegation of copyright infringement poses an incredible threat to the music industry as a whole. The artists claimed that “the judgement is certain to stifle creativity and impede the creative process” because it “threatens to punish songwriters for creating new music that is inspired by prior works” in the amicus brief written by music attorney Ed McPherson.

The brief had no effect on the verdict of the case, and the court ruled in favor of Marvin Gaye’s children and estate. This shocked the entire music industry and brought up questions of Marvin Gaye’s own influences, such as Nat King Cole and Frank Sinatra, as well as the musical influences of many other artists – both past and present.

The trial undoubtedly blurred the lines of copyright infringement for the music industry and those who are a part of it, dividing individuals of the industry from the laws that govern them and their sounds. Overall, such a trial poses a greater question to the topic of borrowed sounds, artist influence, and the rules that regulate the creativity involved when making new music.

Despite the rulings of the 2015 trial, musicians and creators continue to draw influence from the music of the past and their modern-day counterparts. Crossing the oft-dividing borders of musical genres, these borrowed sounds link A$AP Rocky’s 2018 rap-pop fusion “Sundress” with Tame Impala’s trippy alternative-sounding “Why Won’t You Make Up Your Mind?” from his 2010 debut album, InnerSpeaker. Members of 1D fandoms who have an ear for the classics are able to hear the heavy influences Harry Styles’ “Woman” draws from Elton John’s “Bennie and the Jets.” As more music is made, more examples of this musical normality of using others’ sounds surface, and the ties that connect musicians, creators, and fans to their common music and to each other strengthen with each new single and album that hits the charts.

This practice of borrowing beats and lyrics does more than just giving an already-used sound a fresh take — it makes music inclusive. It brings music together. And by doing that, it brings people together.

Committed Kanye stans stunned at a first-time listen of Cher’s “Take Me For A Little While” are introduced to a glimpse of the Goddess of Pop’s glory days and the sounds of the 60s. People who took to Twitter with the #freerocky hashtag are inextricably linked to the wavy, psychedelic beats and unique vocals of Tame Impala. Young girls who ran Harry Styles fan accounts on Tumblr in the 7th grade share a love for a sound that their own parents grew up with in the early 70s.

What some people might call stealing or copying should really just be called good music. The practice of borrowing sounds is the practice of making music, and it’s the art of making music that matters. By calling upon musicians of the past, artists evoke the music that made them, the sounds that were the soundtracks of their childhoods — the beats that filled their heads as they were finding their way to their own creative paradise.

Influence is obvious, and music is meant to be borrowed. Common sounds are common ground in a world that is so easily divided, and despite the gray area around creatively utilizing versus stealing in the musical realm, one thing is clear: Cher writing a Kanye song makes for a big hit.

Steal Like An Artist Playlist:

https://open.spotify.com/playlist/0dNg22bMIYbc5dhtPX0XdI?si=hVA_EcTTQUCDsePu9uZn5w