Plastic Love: Nostalgia for a Nonexistent Time

Internet culture, the YouTube algorithm, and millennial and Gen Z nostalgia turned a 1984 Japanese city-pop song into a present-day viral phenomenon.

Written by Haley Kennis

Photo courtesy of Opus

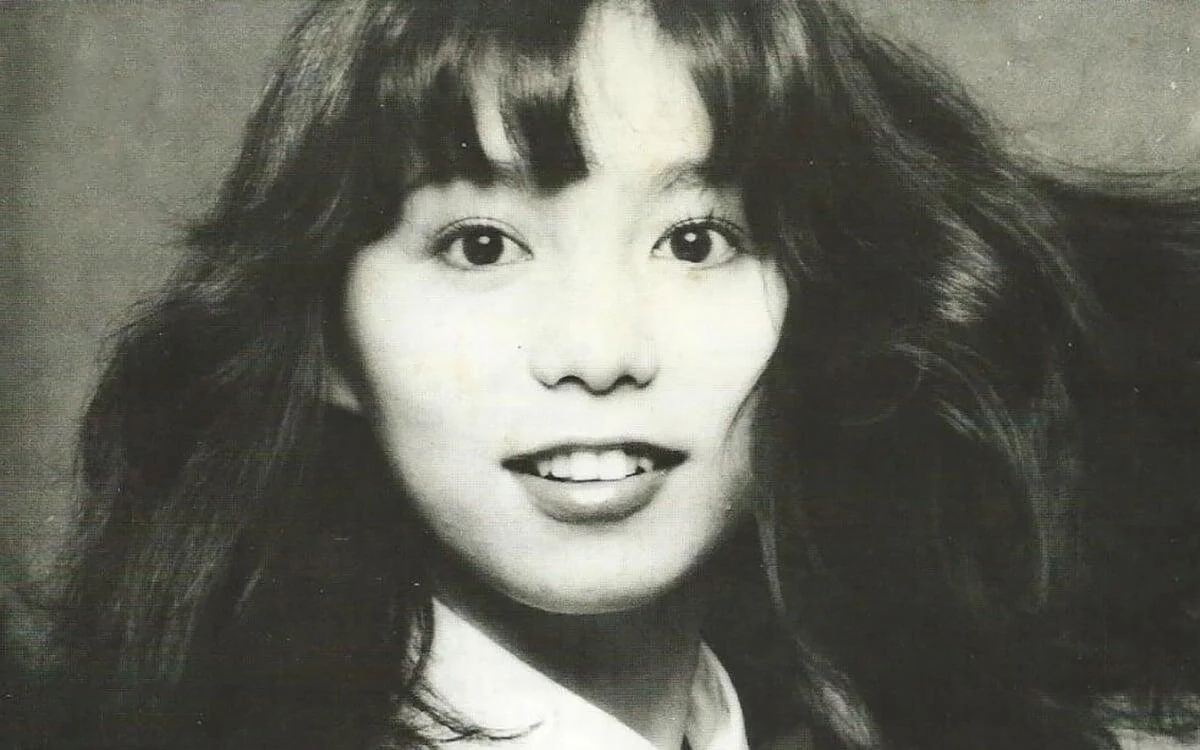

If you have visited YouTube in the past three years, you might have scrolled aimlessly through your “Suggested” videos and found a video titled “Mariya Takeuchi 竹内 まりや Plastic Love” with the above image as its thumbnail and millions of views. Out of curiosity, or just in an attempt to finally get it out of your recommendations, you may have clicked on the video and found yourself quickly captivated by an intro of nearly perfectly-produced strings and piano that bursts into an infectiously catchy, funky bass rhythm. Once the lyrics begin a minute later, it doesn’t even matter if you can understand Japanese or not — the song is timelessly good. Something about “Plastic Love,” originally released in 1984 by Japanese singer Mariya Takeuchi, captured the attention of millions of people from across the world decades later.

The first video to start the chain reaction was an eight-minute long remix reuploaded from a previous channel by Plastic Lover on July 5, 2017. No one quite understands why the YouTube recommendation algorithm decided to promote this specific video to millions of Western users, but it quickly started racking up views. As of October 2019, the video has over 27 million views and counting. For a short time, the original video was taken down due to copyright issues with the thumbnail photo but was reuploaded to another channel, where it earned an additional 13 million views before the original was reuploaded. Since then, the song has been remixed countless times, mashed-up with tracks by Daft Punk, Eminem, Tool, Paramore, and even the “Cory in the House” theme song. It has also inspired hundreds of pieces of fan art of the cover and a fan-made English translation version, and had an official music video produced and released in May 2019 — 35 years after the song first came out. The hype around “Plastic Love” transcended from an ironic meme into a genuine fanbase for the song, Takeuchi, and other music like it.

Photo courtesy of Arama Japan

Though not commonly known to most of the Western audience that grew to love her in the late 2010s, Mariya Takeuchi is a Japanese pop legend. In an article by Japan Times, Takeuchi and her husband Tatsuro Yamashita are described as “the Beyoncé and Jay-Z of J-pop,” producing hit after hit for other J-pop stars, as well as racking up sales of more than 16 million copies of Takeuchi’s albums since the ‘70s. “Plastic Love” was originally included in her 1984 comeback album, Variety, and peaked at No. 86 on the Japanese pop charts. The song fits into the genre of city-pop, which is Japanese music influenced by Western genres like soft rock, R&B, funk, disco, and gospel, with bright horn sections and soaring strings giving the song a lot of its power. However, the eight-minute version known and loved never actually existed in the ’80s — the new extended remix first popped up online in 2017. Either way, Takeuchi is grateful that people are still “waiting and listening” to her music 40 years into her career.

But one question remains — why do so many people who have never lived in Japan, can’t understand the lyrics, and weren’t even alive during the ’80s resonate with this song? The vast possibilities of why this song is so loved may reveal something a lot deeper about our generation.

One influence on city-pop’s popularity with younger generations is vaporwave. Vaporwave was a genre of music largely characterized by remixing old songs from the ‘80s and ‘90s — some of the most popular songs from lesser-known or older Japanese city-pop or J-funk songs that were turned into memes. Vaporwave is also largely influenced by the aesthetics of the ‘80s and ‘90s like neon and cyberpunk, but also symbols of time gone by like classical Roman statues and dead malls. Japanese characters and ‘80s and ‘90s anime also turn up in the vaporwave aesthetic, mainly because the creators think they look cool. The genre popularized songs similar to “Plastic Love” in the United States, like “4:00AM” by Taeko Ohnuki and “Dress Down” by Kaoru Akimoto, but “Plastic Love” has definitely outlived the genre’s popularity.

The lyrics of “Plastic Love” tell the story of a woman who is so haunted by a breakup, she can now only view love as a game, well-aware that she is covering up her loneliness with retail therapy and dancing the night away. This topic is definitely relatable to many young people today, but the lyrics are sung in Japanese, and the vast majority of the comments praising the song say they cannot understand them without a translation. The topic may be extremely relatable to many, but it can’t fully explain why the song blew up the way it did in English-speaking countries.

Many viewers took to the video’s comments section to explain how the song makes them feel. A similar idea is seen among a lot of these comments: “takeuchi’s music literally gives me nostalgia for a timei wasnt even alive in”; “those were the days… that didn’t happen”; “it brings back memories of stuff i’ve never even experienced.” A user named TSG Frank summed the odd feeling up best:

“I think it’s really f---ing amazing how a song like this can have such a strong and characteristic atmosphere that is able to instantly put people in the same specific mind set. Nostalgia for a non-existent time.”

The song’s breezy and energetic city-pop sound is perfect for picturing oneself on a fun night out in the city, distant and free from life’s problems. But people who were born in the 1990s or 2000s clearly never experienced that era and have to imagine that world. The movies, music, fashion, and aesthetics of the ‘80s that are fondly remembered today become our main frame of reference for imagining the decade, and we filter it through rose-colored glasses. We are distant enough to picture the decade as a time of feathered hair, neon, synthesizers, and MTV, but we also know deep down it was more complex than that. All the mediocre and boring music and media is forgotten, societal issues are glossed over, and it starts to look like a better and simpler time than today. It is even more difficult for Western fans to picture the ‘80s in a culture so different from their own, like that of Japan, if they have never visited the country or read its history. But that is not enough to stop young millennials and zoomers from enjoying the fantasy of standing on neon-lit streets in Tokyo, listfully dreaming of lost love.

The title of “Plastic Love” is almost too fitting: young people listen to the song and imagine fake memories of a time they love, but that time never really happened. Maybe the turbulence of the 1980s feels more extravagant and interesting than the 2010s, and we look to the past to try and experience a time where things felt more real. We also know that it’s just nostalgia talking, and in ten years’ time people will start looking back on the 2010s with a similar fondness when new problems arise in society. We are just “playing games,” we know “it’s plastic love,” but we continue to dance to the song and picture that fake world. “Plastic Love” by Mariya Takeuchi struck a chord with millions and continues to do so to this day. While we may never fully understand why the song blew up so suddenly three decades later, we can understand that the song is special enough to transcend language, borders, and time, and that it allowed millions to connect with one another and fantasize about a better time, even if that time is fake. Maybe that love isn’t so plastic after all.