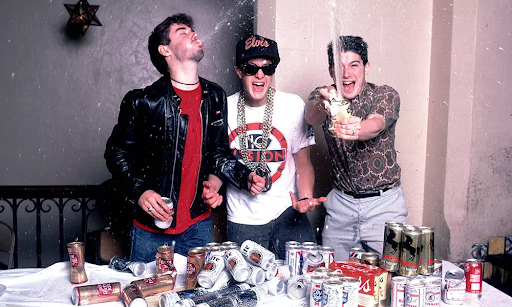

Album Anniversaries: 35 Years Later, the Beastie Boys’ ‘Licensed to Ill’ Remains an Important, Yet Questionable, Part of Hip-Hop History

Beastie Boys’ Licensed to Ill was released 35 years ago last month. Though an undeniably seminal work, and a part of a process that saw the growth of hip-hop’s popularity, some questions about its continued relevance continue to crop up: What did the growth it brought about entail, and what does Licensed to Ill say about that process?

Written by Wonjune Lee

Photo courtesy of Paul Natkin

In a year when Halley’s Comet made its once-in-a-generation trip past Earth, the Chernobyl nuclear reactor exploded, and the Space Shuttle Challenger disintegrated live on television, rock ruled the airwaves. From radio airplay to Billboard charts and MTV scheduling, hair metal dominated popular music at the time. But even as it was dwarfed in sales by releases like Van Halen’s 5150 and Bon Jovi’s Slippery When Wet, one debut album offered a glimpse into the future of pop music — a future that it didn’t invent, but instead appropriated and molded for a very specific audience. Licensed to Ill, released in 1986, marked the debut of the Beastie Boys and signaled hip-hop’s entry into the white suburban teenage bedroom, far away from the Black communities for and in which the genre had originated.

Nothing captures the atmosphere of Licensed to Ill quite like its two most well-known tracks, “Fight For Your Right” and “No Sleep Till Brooklyn,” and, in turn, nothing quite captures those songs like the music videos made to promote them. In creating a celebratory, party atmosphere of rebellion, the videos highlight the image that the Beastie Boys wanted to create for themselves, while also giving us a glimpse into the demographic that the group was primarily promoted to.

“No Sleep Till Brooklyn”’s foray into MTV satirizes the glam metal culture of the ‘80s, making fun of tropes like big hair and zany costumes that were commonplace in metal shows of the era. It constantly attempts to pose the Beastie Boys as something new and different, wearing fashions distinct from the glam metal bands that were everywhere at the time, mixed with an explicit disdain for 80’s rock. Ironically, the criticism of glam metal in “No Sleep Till Brooklyn” seems misplaced when juxtaposed with the music video for “Fight For Your Right,” in which loud, angry rapping is all that keeps it from being reminiscent of a typical metal video. Its main theme is teenage rebellion against authority — which had long been pop metal’s bread and butter — featured in other music videos from acts ranging from Twisted Sister to Night Ranger. In both music videos, it is clear that the Beastie Boys were being marketed to a very specific audience that is accustomed to a rebellious ethos and for whom its rebellious attitude appeals to: white, middle-class teens. After over a decade of popularity in cities, hip-hop was finally entering the suburbs, riding the new, expensive medium of cable.

Looking back on the group in 2021, it is peculiar how it came to be accepted so wholeheartedly into the hip-hop pantheon when so many other white musicians had failed. What exactly differentiates “Brass Monkey” from the widely maligned “Ice Ice Baby?” How were the Beastie Boys able to escape (mostly) unscathed from what would have been justified allegations of cultural appropriation? After all, like the group themselves state in the lead-off track of Licensed to Ill, they were “Rhymin & Stealin,” singing in ways that were not entirely their own. In an interview with Vulture, one of the Beastie Boys members Mike D offered his own explanation for the groups’ acceptance into hip-hop culture. He discusses a time early on in the group’s career where the Beastie Boys attempted to dress like Black rappers of the time, in Puma suits, and “felt like f-cking clowns.” He mentions that event as a time when the group realized that they “had to learn to be themselves,” and that the Beastie Boys’ subsequent sincerity allowed the group to be accepted as white rappers.

Photo courtesy of Random House

While the Beastie Boys’ discography as a whole has been distinct from those of many of their contemporaries, such as in their utilization of rock elements, establishing their brand of sincerity it is not certain whether that applies to Licensed to Ill. Unlike with later Beastie Boys releases, the promotional material for Licensed to Ill (such as the aforementioned music videos) feature the Beastie Boys in “b-boy” attire, which, alongside breakdancing, originated in African American communities. “Rhymin & Stealin,” the apt opening track, tries to paint the Beastie Boys, a group of former jazz-band Jewish kids, as stereotypical gangsters living a life of violence and crime. It’s true that after Licensed to Ill, the group distanced themselves from the party-boy, hard dudes image that they appropriated, becoming better known for dressing like electricians, detectives, or Mr.Spock, rather than stereotypical b-boys. Still, it is important to discuss the distinct lack of sincerity that Licensed to Ill, the work that kickstarted the Beastie Boys’ success, revels in. The Beastie Boys members themselves were not alone in being disingenuous; rather, the entertainment industry overall was complicit in actively appropriating and then ignoring Black artists. MTV, even during its heyday, received criticism for its racist programming that disproportionately highlighted white musicians at the expense of Black musicians, and it’s hard not to look at the high production value of the Beastie Boys’ videos in that context. Licensed to Ill initiated a journey of growth that led to a more genuine brand of hip-hop that the Beastie Boys could readily claim as their own. But on its own, “Brass Monkey” truly does seem more akin to “Ice Ice Baby” than anything else, an attempt to distill hip-hop into party music intended for middle-class teenagers.

It would also be impossible to discuss Licensed to Ill without taking into consideration the album’s misogyny and homophobia, which comes across most glaringly in “Girls,” undoubtedly one of the most misogynistic pieces of music ever recorded. With lyrics such as “I asked her out, she said "No way! / I should've probably guessed her gay” and “Girls – to do the dishes / Girls – to clean up my room / Girls – to do the laundry / Girls – and in the bathroom / Girls – that's all I really want is girls,” the track demeans women and LGBTQ people, and serves as one more track in Licensed to Ill that attempts to position the Beastie Boys’ as “hard,” irreverent party boys. It should be said that the members of the group themselves have apologized for their misogyny and homophobia numerous times after the release of Licensed to Ill, most notably in the track “Sure Shot,” from their fourth studio album, Ill Communication, from 1994. Still, even with later attempts to make amends, Licensed to Ill still cannot be listened to without the context of the culture and attitude the Beastie Boys were appealing to in their debut album.

Image courtesy of Def Jam and Columbia Records

All in all, while Licensed to Ill does not necessarily hold that reputation, it is an album that falls into the category of hip-hop that modern artists of the genre are vigilant against — the type of hip-hop that serves primarily as fun music for white audiences, without acknowledging the type of experiences the genre represents for the communities from which it originates. Licensed to Ill marks an important chapter in music history, one that started the Beastie Boys’ musical and ethical growth and catalyzed hip-hop’s rise in popularity with white audiences. Regardless of how the group matured after its release, their debut album is ultimately an outdated album written by teenagers that promoted outdated values. Licensed to Ill, with its plethora of socio-political faux pas, begs the question — how do genres of music change in order to achieve wider commercial success, and what are the trade-offs of such a change? How should the growth of an artist in their later work affect our view of their earlier music? Licensed to Ill still remains an important part of hip-hop history, but fun and parties aren’t everything it represents.