The Feminine Musique: The New Facets of Video Game Composition

Despite the odds being stacked against them, Lena Raine and Kumi Tanioka’s excellent tracks for Minecraft grow with you anyway. Both composers present a masterclass on how to add on to classic for old fans and the blossoming diversity of gamers alike.

Written by Raymond Lam

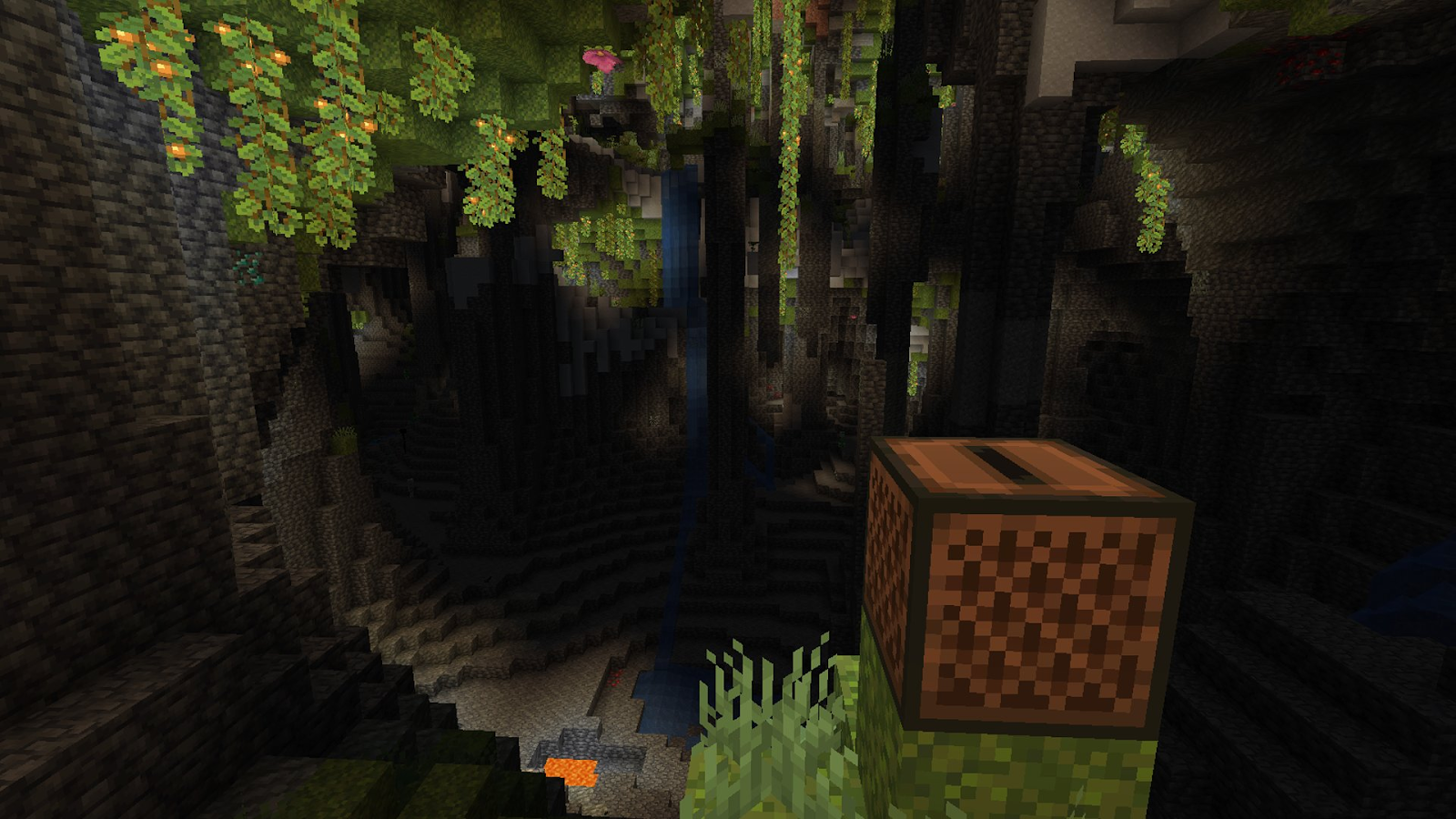

Image courtesy of Mojang

Over the 10 odd years since the release of “Minecraft,” its ascent from a sandbox coding project to the highest-selling game of all time has caused quite the ruckus, with its creative sensibilities bringing the graces of gaming veterans and curmudgeonly Xbox users to the forefront of the 2010s internet generation.

Although “Minecraft”'s virality has since faded from its high point as the game of choice for grade schoolers the world over, its reputation remains strong, especially within the collaborative, creative communities the game has fostered. It’s grown beyond its original scope, now also a veritable art medium for sculpture and worldbuilding — including a virtual replicant of UT Austin's campus — and informative tool used to bypass journalistic censorship abroad, among other things. Its player base has changed with the times as well, with the new “Minecraft Generation” a bit more mature than at the game’s debut (29 years old as of 2016, though trending to age 24 in the past few years) and diverse, with women now making up 40% of its users.

With “Minecraft” not only surviving but thriving, and video game soundtracks becoming a greater part of the public canon, it begs the question: What have the fans of the world’s most-purchased game been tuning into this whole time? And why has “Minecraft” decided to change it?

Like most other indie games, “Minecraft” was scored by just one composer, Daniel Rosenfield (better known as his credited pseudonym, C418). This is a common trend among indie games, giving players a front row seat for the stylistic whims of lone musicians throughout a game’s progression (and perhaps comprising it entirely). C418’s ambient palette of piano and quiet electronica, more genetically related to Erik Satie’s “Trois Gymnopédies” for piano (1888) than contemporary action game scores, has slowly come to represent the hours of nostalgia from the endless hours of playtime users have extracted. Particularly in the vacuum of a linear narrative in the do-it-yourself adventures of sandbox games, the music’s the only truly universal experience to playing “Minecraft”. Largely unchanged, the spacious tracks remind a now grown-up generation of simpler times, becoming the platonic ideal of what modern indie video game composition and nostalgia is supposed to be.

So when “Minecraft”'s developers announced new tracks for the game’s “1.18 Caves and Cliffs II” update that weren’t by C418, more than a few reservations were at hand. Touching a classic of any form of media never goes well with any nostalgia-crazed fanbase, conjuring visions of media lost in translation or a poorly executed Netflix reboot. Now that 2010s kids are approaching their golden years and rediscovering new changes to the game (Axolotls? Isn’t it too soon for C418 Nostalgia? And what’s a Dream SMP?), “Minecraft” purists have usually held a firm resistance against any changes, soundtrack or otherwise.

The success of Lena Raine’s initial commissions for “Minecraft”’s soundtrack during the “Nether” update in 2018, then, could not be more exciting. Though largely known for producing more sparkly, action-packed 8-bit tracks in homage to retro platformers of years past, Raine’s newly commissioned environmental tracks were tailored for a revamp of the game’s lava-ridden, oppressive (and, until recently, unaltered) interpretation of Hell. Capacious, droning MIDI synths and looping piano motifs on tracks like “Rubedo” now fill the void, accompanying players as they explore revamped, newly revived environments added in one of the game’s few changes to its “Nether” dimension.

It seems like the changes have gone over especially well, then, considering Lena Raine’s return and the recent recruitment of “Final Fantasy” composer Kumi Tanioka, this time for changes to the game’s rather static underground environments for its “Caves and Cliffs II” update.

Part of their success arises from their relative tenure in video game composition, a rarity within traditionally male-dominated game development. “Celeste”, the cutthroat retro-platformer Raine’s best known for, orchestrates all-consuming synth swells to envelop usual piano “raindrops” in pivotal moments for a poignant take on the on anxiety and mental health subtexts of the game’s narrative. Tanioka’s work, too, is a calmer retake on old classics, using breathy digital flutes as the primary motif in “Final Fantasy Crystal Chronicles”, a spinoff of the original classic “Final Fantasy” Japanese role-playing game series. By and large, their work is excellently tailored to a more peaceful, less adrenaline-driven revision of gaming classics.

It’s especially heartening to see both composer’s tracks being so well-received in both video game production and classical composition (where 1.8% of performed works are by female composers), with the tracks of both Lena Raine and Kumi Tanioka’s work simply seen as new directions for the long-running franchise. Free from the constraints of a larger public presence (C418, Raine, and Tanioka only show up once in “Minecraft”’s end credits), new fans have been quicker to liken themselves to tracks taken at face value in both the “Nether” and “Caves and Cliffs” changes to the game.

With limited storage space and attention spans to work with, earlier retro games often employed frantic, memorable looping melodies designed to immerse players in spite of the analog aesthetics of the systems available at the time. Translated into their music, the games’ limited soundfonts and repetitiveness gained their own charm, even as technological limitations were eased.

Ironically, as indie games like “Minecraft” grew into much-improved storage formats and storytelling capabilities, they retreated into a more minimalist tradition, with C418 borrowing from the earliest games’ minimalist philosophies to keep background music as something for the user to impress their own perspectives on. As such, it’s partly why games like “Minecraft” have been so pervasive for the recent resurgence in gaming, its approachability allowing a greater diversity of players to finally try out games more openly.

It’s in this subtlety that composers like Kumi Tanioka and Lena Raine thrive: Raine’s tracks have a more active, adventurous electronic sparkle, while Tanioka’s more classical ambience blends seamlessly with C418’s spacey piano leanings. The placement of the new music is quite apt as well: the tracks are designed to play in select environmental biomes for players to explore. Raine’s “Infinite Amethyst” is limited to the rare Grove and Dripstone Cave biomes, while “Comforting Memories” is exclusive to the Grove biome. Raine and Tanioka’s tracks present a marked departure from C418’s characteristic sound, but they aren’t out of place either. As players explore new areas of the game, they’re free to find new, uncharted environments and tracks for the blank canvas of discovery the game presents.

Image courtesy of Mojang

“Minecraft”’s approach to changing its modern classic of a soundtrack presents quite a bit to learn from. Even beyond Raine and Tanioka’s successes in the male-dominated nature of video game composition, it’s enough to simply acknowledge the more open-ended philosophy and freedom inspired by games like “Minecraft.” Both composers’ welcoming and inviting tracks, perfectly integrated with the original games philosophy, reflect the new faces of a blossoming player base and give a new diversity of players the freedom to explore “Minecraft” at their own pace.