America Giveth and America Taketh Away

The country’s music serves as a beacon of freedom, but not even that is safe from its cynicism.

Written by Wonjune Lee

Illustrated by Micaela Galvez

In Crooked Media’s “Wind of Change,” one of podcasters’ favorite productions of 2020, author and investigative journalist Patrick Radden Keefe follows a rumor he heard from an ex-Central Intelligence Agency officer while researching one of his many stories: that “Wind of Change,” a hit song by the West German hair metal group Scorpions, was actually written by the CIA and disseminated throughout the Eastern Bloc to weaken communism.

Although Radden Keefe’s findings didn’t allow him to definitively conclude whether “Wind of Change” was actually written by the CIA, one thing is made extremely clear: it wouldn’t be out of the question. The possibility is beyond disheartening not just for Scorpion fans, but fans of music in general — people like my dad and many others who grew up jamming to the Scorpions’ biggest hit, “Rock You Like a Hurricane,” even when it was a felony to do so.

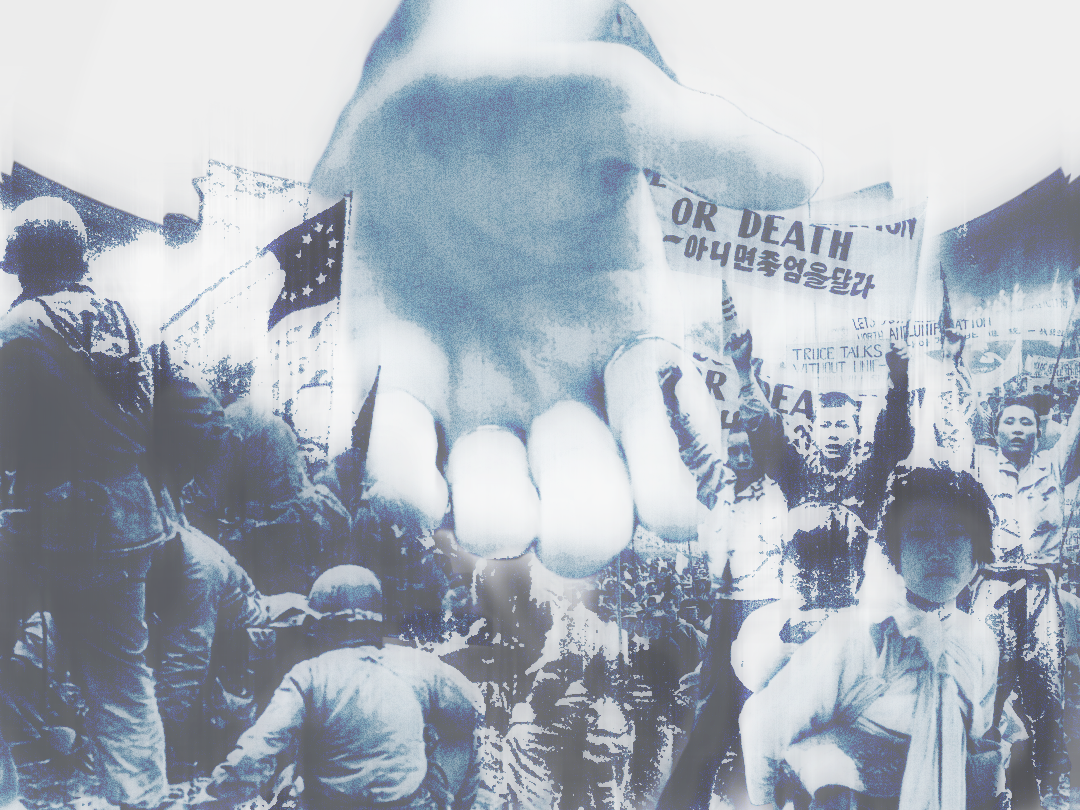

South Korea has always been a member of ‘the first world’ — a group of nations aligned with the United States, that, in Ronald Reagan’s words, “free societies … responsive to the needs of the people.” Yet, like many members of that club, South Korea was far from a bastion of liberty for much of the Cold War. From the end of the Korean War until a democratic revolution in 1989, South Korea was ruled by a succession of military dictators who had no love for freedom or democracy, and yet were backed by the United States, both politically and militarily.

When looking through my dad’s record collection from the time, it’s hard not to notice that many of his records are missing important tracks that were censored, banned from both sale and broadcast. There were a myriad of offenses for which music could be banned; It could be for suggesting resistance against authority, for espousing left-wing political views, or otherwise for being “morally damaging.”

Often, these standards were extremely ambiguous, and they often weren’t applied consistently — for example, John Cougar Mellencamp’s “Jack & Diane” was scrubbed off for depicting teenage sex, while Olivia Newton-John’s “Physical” was allowed on store shelves. Queen’s otherwise innocent “Bicycle Race” was banned for the line, “I don’t want to be the President of America;” ABBA’s “Money, Money, Money,” a criticism of capitalism, was banned for promoting materialism; and the entirety of Pink Floyd’s The Wall was banned for pessimism. The list goes on.

Other times, new tracks, called “wholesome popular music,” were added to albums. One famous example is “Ah, Republic of Korea!” by Soo-ra Jeong, a song that paints South Korea as a beautiful land of opportunity where “all dreams can come true.” Ultimately, even these heavy-handed measures couldn’t stop Korean youth like my dad from consuming contraband culture, most of which was American. One huge loophole was the presence of U.S. military forces on the Korean peninsula, along with the American Forces Network, which broadcasts American radio and television content without oversight from the Korean government. A U.S. military apparatus served as the hole in a fence built by a U.S.-backed military government.

America holds a special place in my dad’s heart to this day. While his generation led the political movement that ended the U.S.-backed dictatorship, he still views America as a place where crazy bands like Mötley Crüe could release music and where artists like Bob Dylan could become folk heroes. But in the end, it’s hard to tiptoe around the fact that America, the birthplace of Bruce Springsteen and Woody Guthrie, played a part in creating the unfree society he grew up in, still maintains a reverberating influence in Korea to this day. After all, I probably wouldn’t even have known what “Wind of Change” was without him.

As a cultural entity, the United States (especially with its most self-critical works of art) promotes America as a place for individual expression. However, America as a political entity often does the opposite. It’s part of a larger complicated relationship many non-Americans have with the U.S. Many of us would like to believe that America has a positive influence on the world, even when it is at its most cynical. And that’s why the idea presented in “Wind of Change” — that even what we non-Americans believed was largely separate from America’s cynicism could be directed by it — is such a chilling one.