The Ultimate Art and Music Playlist: Shoegaze Edition

Prepare to fall in love again, channel your teenage disillusionment, and dance shamelessly in these pairings of emotional art pieces and distorted, dreamy songs.

Written by Antonio Arizmendi

Image courtesy of Adelphi

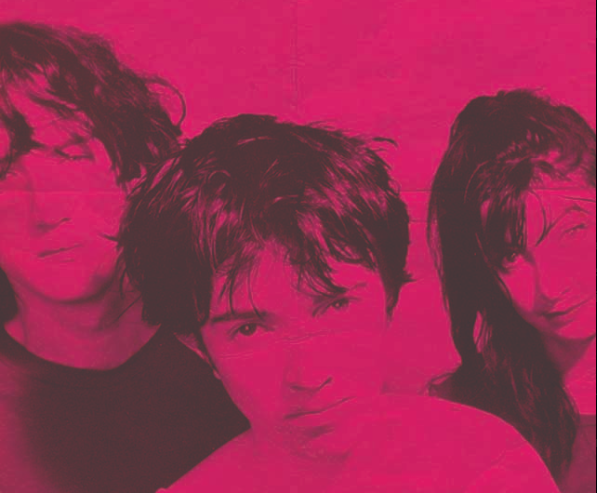

Shoegaze, a genre of rock dependent on droning guitars and reverb-laden vocals, occupies its own ambiguous landscape. Dynamic and abstract, the sounds of shoegaze encounter a constant dialogue with distortion. Guided by bands like Slowdive and My Bloody Valentine, the listener is led into an environment of dynamic sounds ranging from melancholy to overwhelming verve.

Cultivating their craft in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, Shoegaze artists realized the creative strength of fusing sight and sound. The genre’s traditionally fuzzy, distorted album covers, evocative of its musical attributes, perfectly coincided with the experimental art of the time. As blurry expressions melded and impacted one another, a new artistic experience was made. Following that synthesis of art and music, here’s a list of hazy shoegaze sounds and their dynamic visual relatives.

“Larmes (Tears)” by Man Ray and “Into Me” by Glare

Photo courtesy of Getty Museum and image courtesy of Sunday Drive Records

Our first pairing is tearful — literally. A silver screen actress peers into a spotlight in Man Ray’s photograph, with each tear abnormally exaggerated to the size of glass beads. From the heavy lashes to the solitary droplets, Man Ray aestheticizes beauty in agony. A product of one of the artist’s breakups, Larmes commands a certain hopelessness, those swooning eyebrows searching for resolution.

Glare’s “Into Me” mimics the act of crying by progressing from a hazy sadness to an explosion of emotion. Peaceful strumming drags on toward the beginning, providing clarity and silence before the chorus’ tearful storm, with an obscured bass hinting at doom. This pensiveness, through peeks of cymbals and a building tempo, erupts into tears. With six compact lines of elongated lyricism, a ghostly voice echoes, “I am / Who I believe to be,” as the singer tries to cope with a destructive relationship they describe as a “disease.”

This cryptic expression in the lyrics hints at a decentralized sense of self. It is this search for meaning in the midst of life’s cruelties — a performance gone wrong for Ray’s heroine and a relationship destroyed for Glare — that ties both works into sadness. Each pounding drum, each tear, beckons us to experience loss again and again.

“Requiem” by Helen Frankenthaler and “Sometimes” by My Bloody Valentine

Images courtesy of The Helen Frankenthaler Foundation and Angus Cameron

Frankenthaler, an abstract expressionist, moves the viewer with an imposing block of dried blood, each brushstroke representing a change in “melody.” The immediate gloom of the dark zone , a reference to funerary meditation (the titular term, “Requiem,” is a funeral mass), is offset by a glowing purple and red spot. From an awe of bleakness comes the vibrance of life.

The shoegaze classic, “Sometimes,” illustrates this idea sonically. Distorted guitars, like the muddy, tense maroon of “Requiem,” place the listener in an anxious fugue state. A synth introduces a whimsical line, with airy tonal progressions rising against the onslaught of monotone reverb. Kevin Shields decentralizes his lyrics, making his alto voice an elevated instrument of the sonic landscape.

In both works, the artists find beauty in daunting forces, whether it be a melody of love or vitality.

“Monk by the Sea” by Caspar David Friedrich and “Inside Out” by Duster

Images courtesy of Alte Nationalgalerie and Numero Group

Duster’s “Inside Out,” a mellow spin on the shoegaze genre, is undoubtedly meditative. A resonant strumming provides the basis of the song, with distant, soft vocals sharing the monotone nature of a Buddhist koan. Mellow lyrics describe a fascination with a girl “slow and deliberate / With her words,” words so infused with love that it makes the vocalist “fall apart / From the inside out.”

In Freidrich’s painting, there is also a sense of peace. The monk who stands by a calcified shore fades into the dark ocean, becoming insignificant in the scope of the morphing blue sky. The viewer may feel a deep sense of wonder seeing the forces of nature, a sublime sensation that seems to block out any earthly anxieties. There also lingers a sense of ambiguity in the darkness. Not terrifying, but entrancing and welcoming.

Both works are so vividly quiet in their atmospheres, depicting a deep absorption in the world of nature or the rapturous calm of love.

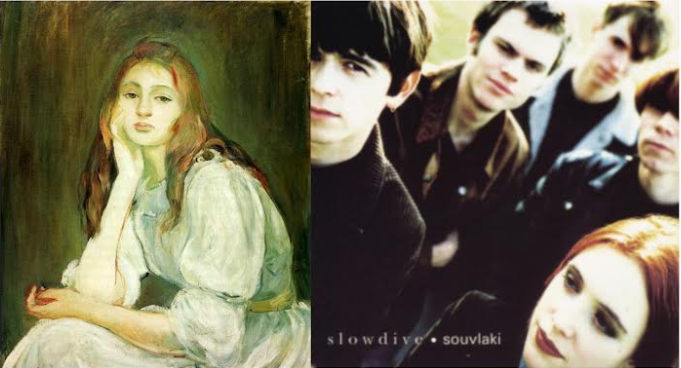

“Julie Daydreaming” by Berthe Morisot and “Alison” by Slowdive

Images courtesy of Bridgeman Images and Creation Records

Berthe Morisot painted this portrait of her teenage daughter in 1894. Chin on her hand, Julie looks uninterested. Apart from our world, her distant gaze and downturned mouth anticipate the challenges of adulthood. A muddy aura in the background reinforces this fatigue, while the fresh, green highlights in Julie’s dress call back to her juvenile potential. In this wistful teenage portrait, the confusion and dread of growing up is familiar even today.

Similarly, Slowdive’s psychedelic ballad “Alison” calls back to the complexities of youthful exploration. Haunting in its dreamy chorus and melodic distortion, “Alison” aesthetically implies a spiraling romance.. Lyrically, the narrator is eerily aware of Alison’s love of pills, but conflictingly states “Your messed up life still thrills me.” A haze of lyrics show the almost psychedelic nature of a drug-laden escapade with “TV-covered walls” and "the sailors strik[ing] poses.” This trippy visual is made more melancholic by the repetition of an abysmal line, “Alison I’m lost,” a lyric that echoes and fades like the girl’s “messed up” world.

As someone listens to Slowdive’s Neil Halstead lyrically surrender to Alison’s psychedelic escapism, the painting of Julie may become more provoking. When the innocence of childhood fades away, who can blame Julie, Alison, or any adolescent for their disillusionment with reality?

“The Sugar Shack” by Ernie Barnes and “Heaven or Las Vegas” by Cocteau Twins

Images courtesy of Ernie Barnes Family Trust and 4AD

The Cocteau Twins are legends in the world of shoegaze for a good reason. The bright, rhythmic “Heaven or Las Vegas” deal with the eccentricities of life through upbeat tempos and soaring, hazy guitar riffs. Elizabeth Frazer, the band’s vocalist, lets loose with soprano distortion, each lyric depicting the thrill of loving “a boy that won’t love” her back to “singing on [Las Vegas’] famous street.” This excitement — the colors, sounds, and characters of a vibrant place like Sin City — becomes a certain heaven in itself.

A similar surge of dopamine accompanies the vibrant dance of Barnes’ “Sugar Shack.” Elongated limbs reach for the sky and lean into one another in a celebration of Black joy and expressive dance. The eye roves around endlessly, finding seemingly infinite amounts of figures in unique states of euphoria. The characters in Barnes’ piece encourage observers to get up and dance with them, incorporating each viewer into the celebration.

One can almost picture Frazer singing in the dance hall, reveling with others in the spotlight of spontaneity. Against a more dim outlook on reality, “Heaven or Las Vegas” and “Sugar Shack” decidedly advocate for joy.