Bad Religion: Unearthing the Spiritual Transcendence of Leonard Cohen

Leonard Cohen emerged as a folk icon in the 1960s, weaving themes of religion and spirituality into his songs and poetry throughout his career. His art serves as a timeline of a man seeking to make sense of the world.

Written by Joseph Gonzalez

Photo courtesy of Jack Robinson

Leonard Cohen’s work reads as a lifelong plea to God from a man deeply entrenched in religious orthodoxy and spirituality, struggling with the natural temptations of the human condition. Religion served as a lens through which Cohen interpreted his life, imbuing his poetry and songs with a weight that transcended the triviality sometimes found in popular music. Cohen’s raw, monotone voice delivered an unapologetically honest perspective that was new to the music scene of the 1950s, and his lyrics, whether infused with humor or despair, ingrained themselves within the memory of the listener.

His first heroes were poets, particularly those in the Transcendental movement of the 1830s and ‘40s. The works of writers such as Walt Whitman, Jack Kerouac, and Federico García Lorca — after whom he named his daughter — left a lasting effect on a young Cohen trying to find his artistic voice. He decided to major in English when he attended McGill University in Montreal, Canada. At just 22, Cohen published his first work, a poetry collection called “Let Us Compare Mythologies.” Even in his first work, his obsession with religion, sensuality, and despair was already evident, establishing the somber and reflective style that would define his work.

In his poem “Prayer for Sunset,” Cohen writes, “The sun is tangled / in black branches, / raving like Absalom / between sky and water, / struggling through the dark terebinth / to commit its daily suicide.” Inspired by the biblical story of Absalom’s tragic fate, the poem evokes the tension between light and darkness, reflecting Cohen’s struggle to find meaning in the world.

Growing up in an Orthodox Jewish household in Canada, Jewish theology was an inescapable part of Cohen’s life. Both of his grandfathers were leaders in the Jewish community — his maternal grandfather was a rabbi, while his paternal grandfather was president of the Canadian Jewish Congress and founder of Canada’s first Jewish newspaper. Strict religious observance colored Cohen’s early life and childhood, reflected in his father’s heavy involvement in Jewish life. However, the published poet’s father died when Cohen was 9 years old. Cohen’s mother, Marsha, was left to raise him and his sister. The loss of his father deeply impacted Cohen’s psyche as much as religious practice did. In an interview with Rolling Stone, Cohen stated, “The death of my father was significant, and the death of my dog were the two, I would say, major events of my childhood and my adolescence.” There’s an undercurrent of melancholy that runs through Cohen’s work, as he seeks transcendence not only through religion but through romantic desire, which, in itself, mimics religious desire.

“Suzanne,” one of Cohen’s most iconic works, was inspired by Suzanne Verdal, a dancer (not to be confused with Suzanne Elrod, with whom Cohen later had children). In the song, Cohen elevates Suzanne to a figure of religious importance and transcendental beauty similar to Jesus Christ. Cohen plucks his guitar, his words accented by a beautiful choir of female voices, who often repeat his words or respond with a syncopated hum. Addressing Suzanne, Cohen sings, “forsaken, almost human,” describing how Jesus “sank beneath your wisdom like a stone.” This idealized portrayal of Suzanne reflects Cohen’s subjective opinion of her but invites listeners to meditate on her as one may meditate on the religious figures of the Buddha or Krishna. Ruminating on religious figures or ideas can draw someone closer to the perfection that they represent. “You’ve touched her perfect body with your mind,” Cohen praises. His experience with Suzanne reaches an ineffable perfection through cerebral awe, rather than physical desire, establishing a religious fixation for her.

Cohen released his masterwork, “Hallelujah,” in 1984, forever connecting him to the Hebraic exclamation. In the same year, he published his most ambitious volume of poetry, “Book of Mercy,” a collection of 50 numbered poems that read like contemporary psalms. This sprawling book of prose transports the reader to centuries in the past while retaining a timeless quality. Cohen, like in his songwriting and previous poetic work, explores themes of love, loss, and despair, but this time with literal biblical significance.

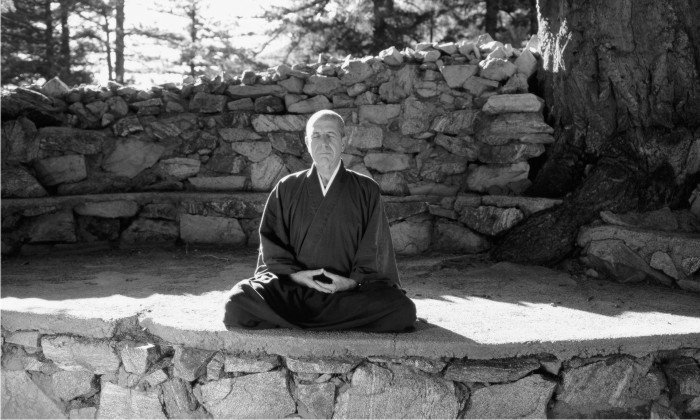

Anyone who followed Cohen’s career even moderately closely could detect the contradiction between his favorite themes of lustful desire and religious asceticism. While Cohen would never totally abandon his desires, he took a significant leap into ascetic life when he joined a Buddhist monastery in Los Angeles at the age of 60. At a low point in his life, amid acute clinical depression and alcoholism, Cohen's long-time acquaintance, Zen Master Kyozan Joshu Sasaki Roshi, pulled him into the Zen monastery located on Mount Baldy to reset his mind and body in monastic life. “I had a great sense of disorder in my life of chaos, of depression, of distress,” Cohen told NPR in 2006.

After a year in the monastery, Cohen became an officially ordained Zen Buddhist monk. His newly strict lifestyle forced him to shed his materialism and desire for unnecessary external pleasures. Monks follow a strict schedule, which includes getting up at three in the morning and meditating for hours each day. Cohen would still find time for self-expression, however. Throughout his five-year stay, he constantly drew and wrote short poems that would eventually end up in his well-loved 2006 collection, “Book of Longing.”

Photo courtesy of Zenkan

After leaving the monastery, he spent a year in Mumbai studying with Ramesh Balsekar, a Hindu teacher specializing in Advaita, a non-dualist tradition of Hinduism. Cohen emerged from these experiences with a new clarity of perception. “What happened to me was not that I got any answers, but that the questions dissolved,” he reflected in an interview about Ramesh Balsekar on his shift in perspective.

Emerging from this self-imposed hiatus of enlightenment, Cohen released Ten New Songs, an album that reads as a softer version of the sound he crafted in the late ‘80s. Peculiar synths and the beat of a drum machine underscore Cohen’s somber yearnings.

In “Alexandra Leaving,” Cohen employs Christian imagery to articulate a lost love, similar to the narrative of “Suzanne.” He sings, “And you who were bewildered by a meaning / Whose code was broken, crucifix uncrossed / Say goodbye to Alexandra leaving,”. Cohen duets this slow, swaying ballad with frequent writing collaborator, Sharon Robinson. Their voices seem to mold together into one, supported by a seductive, sustained synth, delicate strings, and a steady drum beat.

The collaboration between Cohen and Robinson, who sings with Cohen on every song of the album, defines Ten New Songs. His collaboration with female singers shaped his sound throughout his career. Cohen valued the interplay between masculine and feminine energy within his music, a balance that is central to the cosmology of Kabbalah, the form of Jewish mysticism that Cohen studied.

Cohen continued to create, even in the last years of his life as he suffered from major chronic pain. Living with his daughter, Locra, he was largely bedridden, finding solace in writing poems and lyrics as touring and performing became impossible.

In 2016, he released his final album, You Want It Darker. This collection of songs was the darkest of his career, in which his gravelly voice comes across as frightening, conveying an eerie foreshadowing effect. The soft-spoken lyrics highlight the power of his words, a reflective reminiscence of a man acutely aware of his mortality. The title track, “You Want It Darker,” is the most prominent on the album. It features his ominous voice, accompanied by a brooding bass line, a sparse organ, and eerie backing vocals resembling a Gregorian chant. Written as an address to God, “You Want It Darker” captures Cohen’s acceptance of his painful condition as fate.

“Magnified, sanctified / Be the holy name / Vilified, crucified / In the human frame,” Cohen sings, acknowledging the inevitable destruction of the impermanent human form. “You want it darker / We kill the flame.” Even tragedies must be accepted as God’s will according to Cohen. The powerful chorus echoes his profound acceptance: “Hineni, hineni / I’m ready, my Lord.” The Hebrew phrase, meaning “here I am,” reveals Cohen’s full surrender to his faith and the welcoming of death. As he sings these final lines, the sublime sounds of a haunting choir replace Cohen’s voice, with the same hypnotic instrumentals introduced at the beginning of the song. The track ends how it began as the choir fades out on a mysterious chord, the voices still seeming to echo even after the song ends. It wasn’t a plea for escape as much as a necessary leap into whatever was to come next.

Photo courtesy of Graeme Mitchell

Cohen passed away two weeks after the release of You Want It Darker. Posthumously, a collection of poems and another album were released, further continuing his legacy and genius.

Cohen left behind a body of work that addresses the spiritual yearning inherent in self-awareness. Through humor, blunt honesty, and a biblical vocabulary, he offered a little enlightenment to those who listened to his songs, pointing to a purpose beyond the material. His journey was universal, but the way he lived was incredibly particular. As he sang in “Bird On a Wire,” “Like a bird on a wire / Like a drunken midnight choir / I have tried in my way to be free.”