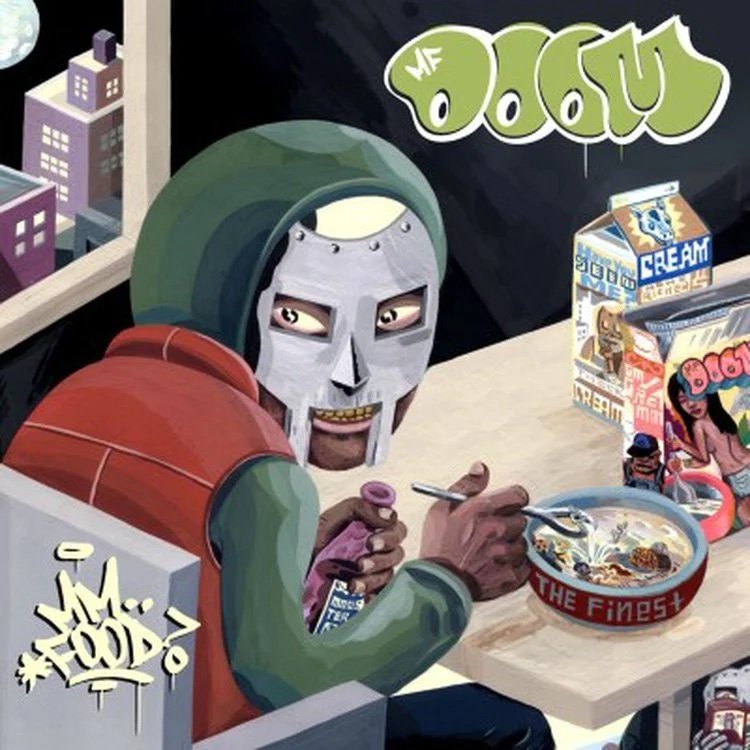

Album Anniversaries: 20 Years After ‘Mm..Food,’ MF DOOM Lives on in Authenticity

MF DOOM, one of the illest lyrical masterminds in the rap multiverse, passed away in 2020, leaving a noticeable hole in Hip-Hop. Now, 20 years after the release of Mm..Food, his music still stands as a keystone in the rap world: poetic, villainous, and wholly authentic.

Written by Rachel Joy Thomas

Photo courtesy of Ross Gilmore

Content Warning: This article contains graphic depictions of violence and self-harm.

Daniel Dumile was known by many aliases — Madvillian, Mr. Lip, Vaudeville Villain, and Metal Fingers, to name a few — but Zev Love X may have been the most impactful, existing as the not-so-alter ego he acquired in the golden-age Hip-Hop trio KMD.

KMD (Kausing Much Damage), comprised of Dumile (as Zev Love X), his brother Dingilizwe (DJ Subroc), and Alonzo Djihuti Hodge (Onyx the Birthstone Kid), produced one high-quality album, Mr. Hood, a comical yet introspective work with conversational discussions of race and class. The trio set itself up for success with another record titled Black Bastards, but tragedy struck when DJ Subroc, Dumile’s brother, died while crossing the Long Island Expressway. Dumile’s life irrevocably changed when he lost his creative confidant. He soon faced another harsh reality: Elektra Records refused to release Black Bastards, citing the album cover’s disturbing imagery of a cartoon character hanging from a noose.

So, Dumile left the rap world for years despite his undeniable talent, grieving and slowly accepting the loss of his brother and the rejection from his record label. The complete censorship of Black Bastards effectively ruined Dumile’s perspective on the rap industry. From 1994 to 1997, he walked the streets, unhoused for an unknown amount of time before eventually finding stability again.

Photo courtesy of The Hundreds

DOOM suddenly resurfaced at unlit open mics at Nuyorican Poets’ Cafe in Manhattan as a career revival. Covering his face with pantyhose, Dumile anonymously stole away shows without any lofty suspicions of his true identity. Eventually, the rapper donned a mask resembling the comic book villain Doctor Doom. He adopted the name DOOM, a reference to being “illest,” but also a nod to his childhood nickname, closely tied to his early days in New York. The mask gave the reborn rapper a sense of control over his narrative and how others perceived him.

"A visual always brings a first impression. But if there's going to be a first impression I might as well use it to control the story. So why not do something like throw a mask on?” he told The New Yorker in 2009.

Doom never returned to Zev Love X after KMD. That name, marred by an industry that scorned him, sat on a shelf alongside 300 others acquired during various projects. Over the years, DOOM shifted like a chameleon, shedding layers of his discography and his new aliases: King Geedorah, Viktor Vaughn, and Danger Doom. While these were technically side projects, MF DOOM remained his primary identity, serving up Mm..Food under that calling card.

Mm..Food, a conceptual rap album using different foods as analogous themes for experimental flows, is an anagram of MF DOOM — an apt title, considering the project’s overall tone mirrors the legendary rapper’s day-to-day mannerisms. The album follows the New York native’s alias, discussing hot-button topics in the rap industry through food-themed metaphors “about the things you find on a picnic,” all loosely tied to Dumile’s personal preferences or American culture. Stereogum considers it DOOM’s best album, and the project received near-universal acclaim. Despite it being one of his most lighthearted works, it ventures into rap commentary with a sense of ease and gravitas rarely found in modern-day Hip-Hop.

“Beef Rap” stands as a keystone in the DOOM’s alter-ego, Metal Fingers’ methodology. The track opens with a sample from the movie “Wild Style,” slowly twisting into DOOM’s comic book origin. A classic horror movie introduction (“Bowery At Midnight”) gradually climbs toward robotic squeals, announcing that “project doomsday,” is complete, an homage to his previous album. A sample from a villainous monologue in a 1981 episode of “Spider-Man,” “Canon of Doom,” closes out the wicked introduction, thus introducing listeners to the album with classic finesse.

Dumile spits the album’s first double entendre with ease, “Beef rap, could lead to getting teeth capped / Or even a wreath for mom dukes on some grief crap / I suggest you change your diet / It can lead to high blood pressure if you fry it / Or even a stroke, heart attack, heart disease / It ain't no starting back once arteries start to squeeze.” These lines introduce the first theme of the album: rap feuds.

“Beef Rap” specifically refers to rappers feuding or having “beef” with each other, a theme the "DOOMSDAY" rapper explores immediately. “Wreaths for mom dukes or some grief crap,” refers both to a line from The Notorious B.I.G.’s track “Gimme The Loot” (“The opposite of peace, sending Mom Duke a wreath”) and alludes to sending wreaths to grieving mothers after fatal feuds. DOOM then closes that snippet by advising other rappers to “change [their] diets” to remove fatty beef. In this case, strokes, heart attacks, and “arteries start[ing] to squeeze” refers to the propensity for beef to go too far and lead to fatalities.

The masked rapper continues this framework in “Rapp Snitch Knishes,” his most mainstream cut from the album. In DOOM’s verse, he flows: “True, there's rules to this shit, fools dare care / Everybody wanna rule the world with tears for fear / Yeah, yeah, tell 'em tell it on the mountain hill / Runnin' up they mouth bill, everybody doubting still.” His verse serves as a commentary on the underground world of rap, warning newcomers to avoid snitching and follow the rules. DOOM references Tears For Fears’ seminal track “Everybody Wants To Rule The World,” an idealistic ‘80s ballad with a clear sunshine overtone, rejecting the notion that those who don’t “follow the rules” have any leverage to rule. The lyricist’s flow on “Rapp Snitch Knishes” heartily connects with themes from “Beef Rap,” reinforcing that rappers should focus on making good music and stay out of drama.

Across the album, DOOM establishes himself as a voice for authenticity in the rap business. His interest in staying away from the dangers of rap feuds, wealth, and status symbols reflects a genuine desire to make good music. But, DOOM doesn’t just articulate authenticity through his rejection of the status quo; he also reverberates it in his subtle title entendres, even when the rapper adopts his most villainous persona, like on “Hoe Cakes.”

On “Hoe Cakes,” the use of J.J. Fad’s “Supersonic” juxtaposes the wicked poet’s articulate beatboxing, creating an addictive sonic fusion. The soundscape rustles with bouncy, upbeat textures, making the villainous wizard’s approach to more nefarious themes feel unserious. On the track, Dumile jokes about keeping “[his] hoes in check,” developing a gravitas or machismo that other rappers often portray without alternate personas. “Hoe Cakes” discusses prostitution, as MF DOOM’s alter ego bemoans his escapades with women.

Image courtesy of Jeff Jank

The rapper slyly pulls off a triple entendre with the line, “But I treat her like a daughter, taught her how to bust a nut,” indicating that DOOM has taught the girl how to defend herself against attackers, taught her to crack nuts open, and taught her about sex. The juxtaposition of two of the meanings — one referring to keeping his sexual partner safe and the other using her as a commodity — makes DOOM seem like a somewhat nefarious lover while also having some caring attributes. The personified Doctor Doom’s comic villainy serves as a palatable excuse for why his references to sex work well, as he feels little need to praise or disparage “Daniel Dumile.” He inflates and personifies different elements of DOOM, creating fictionalized and hyperbolic events that come across as entertaining rather than pompous because the listener is aware the lyrics are fictional.

Simple lines like "I get no kick from champagne / Mere alcohol doesn't thrill me at all” from “One Beer” feel grounded and real despite being small, personal references. Rap music has a long history of champagne references; like Grey Poupon, champagne usually symbolizes success — an amenity that few can regularly afford, but one that can be purchased if they make it in Hip-Hop. The Notorious B.I.G. raps on “Big Poppa,” "The back of the club, sippin' Moët is where you'll find me,” indicating that the rapper earned the financial flexibility to drink champagne while also getting into exclusive clubs without issue.

In contrast, Dumile admits satisfaction with beer. It’s a small but simple lyric that reveals more about him than his persona. The masked poet doesn’t rap about cars, money, or wealth often; instead, he focuses on fictional concepts such as villainy and world domination.

One of the most unique focal points within MF DOOM’s discography is his ability to sharply provide commentary on sociocultural fixations in rap music while straying away from personal association. Mm..Food relies heavily on its initial “food-talk” illusions before it dives into real-world conversations, making them more approachable. DOOM’s character takes the heat for any grievous lines, and any potentially Dumile-esque lyrics comment on the status quo in the rap industry. The overt lack of vainglorious lyrics about Dumile’s wealth or status allows even his most ill of lines to flow sensibly in a world where braggadocious melodies have slowly crawled into humdrum expectation.

MF DOOM tragically passed away in 2020, leaving behind a legendary legacy of superb rap albums with wicked sampling, intricate production, and equally profound lyrical flow. Artists, young and old, look up to the producer's mastery of sampling and lyricism, cementing his profound legacy in the modern music industry.

Rap artists take after the legendary Madvillian, with DOOM representing the all-too-common trope of “your favorite rapper’s favorite rapper.” Tyler, The Creator, for example, brews up various characters like Wolf Haley and Dr. TC when debuting his bi-annual albums, a somewhat similar approach to DOOM’s. Though Tyler’s R&B-laden, sometimes braggadocious style doesn’t toy with supervillains and domination, it is clear DOOM’s methodology influences his work.

MF DOOM also inspired artists from completely different genres, like Thom Yorke of Radiohead, who told Dazed: “The way he free-forms his verses and puts it all together, I don’t think anyone else quite does it like that.”

The audacious rapper’s legacy lives on in his side projects, his relationships with his mentees, and his influence on all those who understood his nefarious lyricism and intriguing, cheesy diatribes. Mm..Food, with regard to his legacy,remains one of DOOM’s most popular albums for good reason — it feels like Dumile at his most authentic, despite his character and the mask. The album stands out with its double and triple entendres, unique themes, and rare sense of authenticity. For someone who remained masked throughout his career, DOOM struck like lightning, completely reshaping the world of alternative Hip-hop.