Bad Religion: The Philosophy Behind ‘Deathconciousness’

Crafted from the minds of Dan Barrett and Tim Macuga as a debut for their band Have a Nice Life, Deathconciousness illustrates the obscure and elusive fact of death and the varying sentiments that accompany it.

Written by Jesseca Romo

Photo courtesy of Cat Jones

Embellished with somber mumblings, heavy rifts coated in reverb, and deafening drums, Deathconsciousness creates a dark atmosphere. The album, situated in sonic dread, discusses death primarily through nihilism, the belief that life is devoid of purpose and all attempts to attach meaning end in vain.

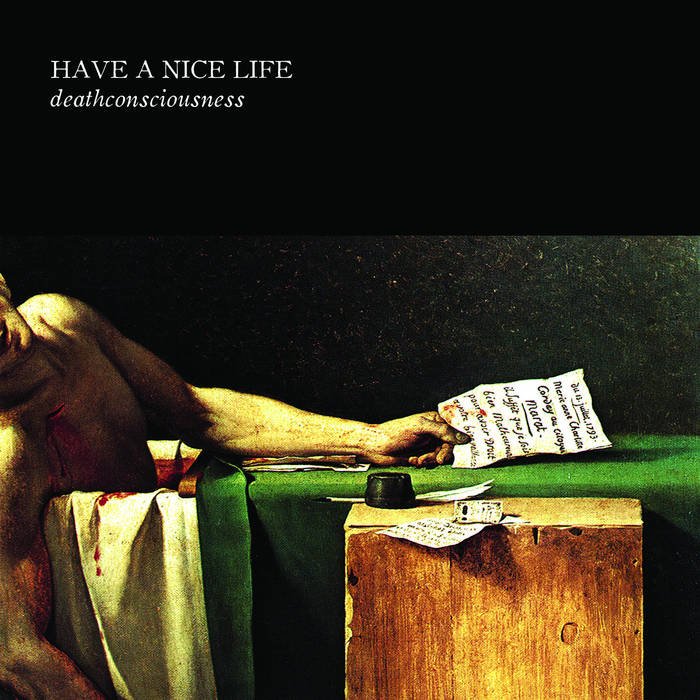

Deathconsciousness initially reveals its philosophical aims on the album cover: a cropped version of the neoclassical painting “The Death of Marat.” The painting depicts the assassination of French revolutionist Jean-Paul Marat, clinging to his assassinator’s letter as he lies lifeless in a bathtub. As Marat, an influential French revolutionary, stretches upon the bathtub in a seemingly peaceful sleep, one comes to understand the power dynamics between death and us. Contrasting Marat’s peaceful position and the splattered blood sprawled across his chest, death becomes the medium between serenity and the brutal reality of the human condition.

Included with the vinyl of Deathconciousness is a 75-page pamphlet that details the story of a cult devoted to the teaching of Antiochus, a pseudo-philosopher figure who spread his philosophy, a philosophy that is best reflected by the modern-day philosophy of transcendental nihilism. Transcendental nihilism differentiates itself from nihilism by asserting that life is meaningless and extinction is inevitable. Best defined in his book “Nihil Unbound,” Ray Brassier states, “Every star in the universe will have burnt out, plunging the cosmos into a state of absolute darkness and leaving behind nothing but spent husks of collapsed matter.” The pamphlet initially mentions the philosophy at the end of the preface, “Even the shattering of molecular bonds, the disintegration of atomic structures, happening in every moment, millions in each nanosecond, everywhere.”

Transcendental nihilism suggests that truth can only be found in death as it pervades all that has and will exist. During one of his public teachings, Antiochus expressed these sentiments, “No joy, no lack of joy, there is no cause and no causes of causes. God, the great Pitier, is not present to keep the tally or to write your name. There is no death. Because there is no life,” and “Because you sought truth and now you have it. Death is truth and truth is death.” The pamphlet also mentions other philosophical concepts, such as determinism, the belief that external factors predetermine our lives. In the album’s material form, the pamphlet further introduces listeners to the perspectives surrounding death that Deathconsciousness details.

Beginning with a 7-minute and 52-second instrumental of droning synths and four repetitive chords, “A Quick One Before The Eternal Worm Devours Connecticut” curates the album's melancholic atmosphere. Unlike other tracks on the album, the song contrasts the post-punk and album’s shoegaze elements with a dreamy instrumental that immerses the listeners in a somber ambiance. Evoking emotions of lingering dread, the track signifies the anguish we experience when contemplating the idea of a life devoid of purpose.

The track mixes into the heavily compressed and distorted wall of sound encapsulated in “Bloodhail.” The hasty transition reflects the complexities of existential dread by contrasting a track that captures a looming feeling of despair with a track that embodies anguish and distress. “Bloodhail” discusses a hunter who desires to cause mass destruction as they come to terms with the continuous, despairing cycle of life and death. This notion becomes clear in the opening lyrics, where the “hunter” states: “And I’m watching all the stars burn out / Trying to pretend that I care.” The hunter knows that everything around them is built to be destroyed, and yet they lack care because it seems futile to do so.

Also described in the pamphlet, the hunter desires to strike god down from heaven. The hunter climbs a staircase built from the bodies of humans linked together, “Faces sweaty, arms and legs / What a glorious set of stairs we make.” The scene represents the transcendental nihilistic belief that even God, a seemingly indestructible figure, will also meet the fate of death. The human staircase reflects humanity’s lineage, each predecessor becoming a stepping stone for future generations.

Image courtesy of The Flenser

On the second side of the vinyl, the beginning track, “Waiting for Black Metal Records To Come In The Mail,” leads listeners to the same interpretation as “Bloodhail” but with an added emphasis on the metaphysical pressures of a highly stratified society. In this song, Dan Barrett and Tim Macuga express their frustration towards powerful institutions and their exploitation of individuals. Lyrics like “A thousand tiny lives / Disappear into the black stretch” and “To propel your national machines / Giving us all the disease, but not the vaccine” leave the lingering feeling of a bleak reality entrenched in servitude. The sentiment of futile concern toward the collective loss of individual lives is now reflected in these large associations that have a greater ability to impact society. Yet, these powerful institutions use their influence to benefit themselves and maximize profit. Hence the lyrics, “There’s no air anywhere / It’s all money now.”

The next song on the album begins with a progressing, beeping synth as heavy drums crash against an overwhelming bass drone. “Holy Fucking Shit: 40,000” is a direct portrayal of determinism. The opening lyrics, “Everything you do is planned out in advance / And the stars push their dark wills down on you,” question the listener’s control over their own lives. The next line, “And wolves all tear themselves apart better in packs / It’s just a function that we will have to work on through,” describes an animalistic side of humanity contrasted with a mathematical function that can simply solve the unpredictable nature of individuals. It reduces human behaviors into patterns that reflect repetitive and predictable actions. This mechanical behavior expresses itself in the lyrics, “We’re machines that eat and breathe / And look really cool.” The track furthers the concept of determinism by depicting humans as machines already programmed with the behaviors and actions we engage in. It implies that humans have no free will and that events occur by external factors out of our control.

Although the album's philosophy follows transcendental nihilism and the existential dread accompanying this philosophy, Deathconciousness still captures the persevering human spirit. Regardless of extinction and the negation of existence discussed in the album, humans have continuously built our society and created lineages of stories for generations. In the song “Telephony,” the narrator deals with grief as they desperately cling to the idea of building a time machine in which they can see their loved one once more, “I can build a door / And I can travel through.” and “If I could just hear your voice / If I could just hear your voice.” “Telephony” explains that grief is a form of unyielding love we have for others even beyond death. Although we exist in a reality of constant death, a brief individual experience of life still finds meaning in its ability to impact others through human connection. It finds purpose in everyone’s individual experiences.

Barrett and Macuga embody the despairing concepts of transcendental nihilism and determinism through their fusion of dark ambiance, distorted riffs, and grainy drums. Today, Have a Nice Life’s conception of nihilism pervades global issues, such as the climate crisis and deep political divide, creating a sense of impending doom. Despite this sentiment, life continues to find ways to prevail, and stars burn passionately. Deathconsciousness teaches listeners that Death, painfully, stands inevitable for all living things, but it does not obstruct that fundamental ability to exist.