Music Without Borders: Bossa Nova is More Than Elevator Music

While bossa nova music brings to mind simple and soft jingles, this notion masks its multicultural and colorful history. Antônio Carlos Jobim brings this Brazilian genre to the forefront, and its optimistic style is a prime example of music and cultural exchange.

Music has the power to transport listeners to cultures and places different from their own. In Music Without Borders, our writers introduce you to international artists, bands, and genres that explore the sounds that bring us together.

Written by Trinity Schroeder

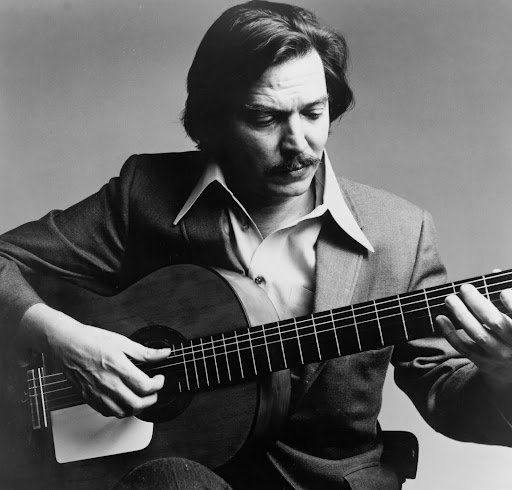

Photo courtesy of Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Ya like jazz? Well, you probably like bossa nova too. Translating to “new trends” from Portuguese, bossa nova creates an identity through the combination of Brazilian samba and American jazz. Its origins are unique to the Brazilian identity, but through the work of Antônio Carlos Jobim, bossa nova became an international sensation. Yet, instead of being heralded as a triumph of cultural connectivity, the child of two energetic genres has been stereotyped as elevator music.

Color, music, and dance are words that come to mind at Rio’s Carnival. This integral part of Brazilian image owes its vibrancy to samba. Samba itself has roots in African drumming traditions. A variety of rhythmic patterns layers drums on top of piano or guitar. From the colonial period of Brazilian history, samba as a form of music and dance became a marker of Rio’s Carnival. Simultaneously, American jazz began in spaces like New Orleans’ Black community Taking inspiration from blues and ragtime, jazz became a staple of American music culture. Following an increasingly globalized post-war period, samba and jazz were able to merge, creating the bossa nova we know today.

During bossa nova’s rise in the 1950s and ‘60s, it’s no surprise that this same period corresponds to a surge in equal rights campaigns and a reclamation of cultural identity. Brazil, with its roots of social and economic disparities facing people of color, revitalizes images of its culture via bossa nova and creates a genre that embodies an optimistic and peaceful aesthetic. Samba and Samba-jazz draw on their Black cultural roots during this time to make the bossa nova fusion. This combination of genres encompasses the cultural wealth of Brazil and adds to their relevance in their birth country.

Antônio Carlos Jobim, also known as Tom Jobim, brought bossa nova to a wider stage through his ability to make this Brazilian genre catchy and relatable. However, his innovative rhythmic themes made bossa nova novel to a new audience. His success as a composer for Vinicius de Moraes’ retelling of Orpheus and Eurydice, “Black Orpheus,” is inspired by the wealth and social inequalities facing Afro-Brazillians of the time. Meanwhile, the bossa nova sound displays the vibrancy of their culture and the Carnival setting. The play’s fame was a launching point for Jobim and popularized the emerging genre. Jobim’s 1967 album with Frank Sinatra and his performance at Carnegie hall put his name in the papers, giving bossa nova its time in the American sun.

Jobim is credited as the “father of bossa nova,” but his privilege as an upper-class white Brazilian differs from the roots of samba and jazz. His ability to take advantage of his education and opportunities is exactly what led to bossa nova’s success. Unlike jazz, which stems from church hymns, enslaved people’s spirituals, and field chants, bossa nova focuses on more dance-like qualities, themes of love and nature creating an air of romanticism. Still, drawing from these origins, bossa nova incorporates the “caboclo,” a Brazilian folk singing style, and instrumentals based on Afro-Cuban and Brazilian music, such as the surdo, which are large bass drums, and claves, that are used as percussive wooden sticks. Through Jobim, bossa nova began to represent Brazil to the world.

One of the most popular bossa nova songs, “The Girl From Ipanema,” paints a romantic beach scene. The light instrumental and soft vocals make the song more intimate. This languidness portrays both the longing and carefree pining of a summer fling. “When she walks, she's like a samba / That swings so cool and sways so gently / That when she passes / Each one she passes goes, ‘Ah.’” The lyrics and tune are laid-back; together they create a nostalgic vision of young love set in the Brazilian summer. Similarly, the song “Aguas de Marco” (Waters of March) takes inspiration from the environment. Its falling pitches and short enunciated vocals paired with the long tones of the accompaniment create a similar sensation to raindrops bouncing off a facade. The repetition of syntax in “A knife, a death, the end of the run / And the river bank talks of the waters of March / It's the end of all strain, it's the joy in your heart” create a catchy and easy-to-follow rhythm.

While lacking the edge in its messaging or even the power of the genres it originates from, bossa nova becomes essentially background music. Some critics even claim that it’s too simple and lacks expertise. José Ramos Tinhorão opined in Hermano Vianna’s “The Mystery of the Samba” that bossa nova “broke decisively with the popular heritage of samba by changing samba’s rhythm.” However, like in “Desafinado,” ironically translating to “off-key,” Jobim specifically targets these critiques. Written to be musically challenging, it shows off the singer’s talent, yet there’s a languidness that’s hard to find anywhere else. The song reverses expectations while embracing the nasal and caboclo style derived from traditional Brazilian folk music that makes the sound unique.

There is no hard truth or commentary from listening to bossa nova, but that is the statement it’s making. When the world says scream, bossa nova says relax. Its existence is credited to the world’s growing exposure to different cultures and people. Its translations into English and the many covers done by American artists like Charlie Byrd and Stan Getz prove the resonance of its themes. But its current use, like in the opening of the 2016 Olympics (Isso Aqui, O Que É?), upholds bossa nova as an integral part of Brazilian culture. Today, bossa nova finds itself still inspiring new musicians. Notably, in rap and R&B, its classical guitar finds its way into songs like “Make Believe” by Juice WRLD. Recognizing its fluid rhythms, artists are able to breathe new life into the genre, making it accessible beyond just tunes in an elevator. However, an entrance from the post-war era into the 21st century seems to reflect how an idea of peaceful coolness will always remain in the background.